Hello again, friends, and welcome to Documentaries for Teens, where I review documentaries on Kanopy for you, the teen! Kanopy is a great source of movies, international works, shows, and of course, documentaries. (How many times is she going to say documentary? So many more times.)

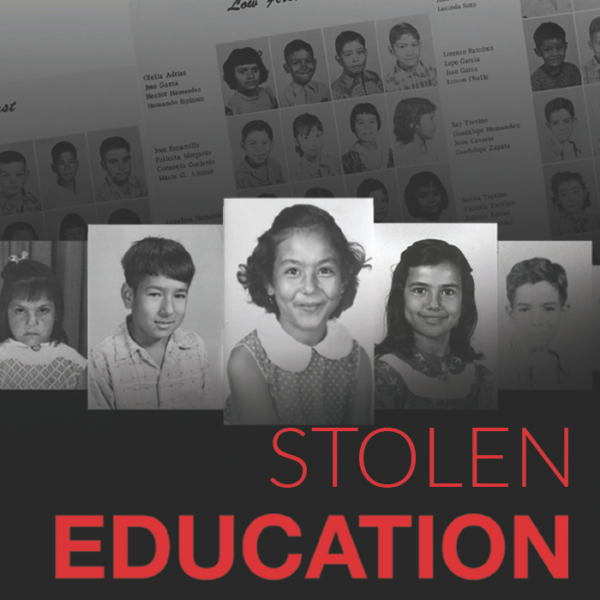

This DOCUMENTARY is a special one. In honor of Hispanic Heritage Month, we will be watching “Stolen Education,” which takes place in Driscoll, TX. In 1957, the GI American Forum filed a suit against the Driscoll Consolidated Independent School District for segregating Spanish-speaking students by a system of beginner first grade, low first grade, and segregated second grade.

During this project, we will meet former Driscoll classmates who testified. They were friends from the Mexican and Texan households, current board members of the school system, and children of the board or teachers at the time of the case.

Laura K. Arnold, a History Professor at Texas A&M-Corpus Christi, explains that the schools, when being pushed to desegregate their schools, attempted to separate students by the fact that they were not English speakers and tried to support this idea by IQ testing. The people trying to implement these policies were the major farmers of Driscoll, who funneled their power by being part of the school board. Why were they doing this? So that the Mexican-American students would break away from education and work for them.

“The only reason they (Mexican Americans) were invited into the community was for them to have labor,” Arnold states.

The Mexican American students were also reprimanded by teachers by being hit by rulers or verbally accosted if they spoke Spanish. This led to the parents not teaching their children how to speak Spanish to avoid the scrutiny they might potentially face.

“I am a great example of that. My parents experienced that kind of punishment,” Arnold states, “They decided ‘I don’t want my children to have this negative school experience, so I am not going to teach them how to speak Spanish so that they succeed in public schools.’ (…) That sense of shame and guilt still remains. You either feel ashamed because you spoke Spanish, or, you feel ashamed because you have no ability to communicate with your great-grandparents or people in your community.”

Mary Schrader was a friend of Mexican American students who testified in the case, as well as the daughter and niece of board members who served during this time.

“We were told, ‘You do not talk to them,’” Schrader recalls. She had been told this by teachers, especially Mrs. Green, who was the wife of Superintendent Green.

“They would take them (Mexican American students) to the office and spank them,” Schrader says.

The primary plaintiff for this case, the one who took this issue to the court, was Albesa Hernandez, a mother of Driscol students.

“The first boy I had, when he went to school, and when school was up (done), he was supposed to be passed five (moved to another grade),” Hernandez says, “In second grade, they passed him to first grade after a whole year. It was supposed to be ‘low first’ they passed him to. I didn’t like it one bit, so I went back to school the same moment he got off, and I talked to Superintendent Green,”

“It’s the law of the school,” Green replied.

That’s when Albesa Hernandez pursued this issue with Dr. Garcia, and DeAnda took the school to court.

I greatly enjoyed this documentary. Every interview had me taking away something and adding more and more to the picture of this town. The interviewer of this documentary really boils it down to this quote, “Unspoken histories that are very real and continue to be with us, people tiptoe around the issue.”

This can be directly aligned with the scope of our history books and our past, how elements are looked over, despite the effects of the matter still prevalent today.

I hope you enjoyed this piece as much as I did, and I will see – or write to you next time in the next installment of Documentaries for Teens. To check out Stolen Education, click the link here.